Quincy Apparel had the makings to be a successful business. The MVP tested using trunk shows demonstrated that the business concept resonated with potential customers. Trunk shows are events, often by invitation only, where garment manufacturers exhibit their creations to an audience of potential buyers. The founders responded to the feedback from early customers to refine their products. A solid growth rate in sales and a high percentage of repeat customers showed that the business had a proven value proposition. Yet the business fell victim to the number one reason that start-ups fail, they ran out of money. But why did such a promising business run out of money?

Let’s learn what Professor Eisenmann believes were the root causes of the business failures, and then I will add my thoughts.

Tom Eisenmann coherently argues that the business failed due to problems with the resources available to the company. Professor Eisenmann does not limit the meaning of resources to capital; he extends the definition to include founders, other team members, investors, and strategic partners. He sums this up as “Good Idea, Bad Bedfellows”.

In respect of the founders, the professor finds two failings: they never decided who was the boss, and they lacked industry experience. The question of who the boss will be is particularly troublesome when the co-founders are friends.

In his book “The Founder’s Dilemma” Professor Noam Wasserman says that over 50% of businesses with co-founders pick friends and family for their co-founders. Rather than the people they know professionally. Prof. Wasserman’s research shows the family or friends co-founder path is the least stable route for a business. It is much more likely that one or more of the co-founders will leave the business early in this scenario compared to businesses founded by professional colleagues. Although Wallace and Nelson swore they would not let the business come between their friendship, they failed to resolve the hard issue of which of them was going to be the boss. They knew having joint CEOs could be troublesome. To the outside world, they split their roles between CEO and COO to keep investors happy. But internally they saw themselves as joint CEOs. This led to unnecessary costs. At times one cofounder would make a change that they felt was within their authority, only to have the other cofounder say “Why was I not consulted, I completely disagree” This meant the decision had to be reversed, a time-consuming and expensive process, which can be deadly when you have limited funds.

Lack of industry experience. Again, like the “who is the boss?” question the founders knew this was a problem.

They sought a partner with industry experience but could not find anyone willing to join the team. This should not come as a surprise; someone with the skills to run a complex operation such as garment production would be in demand.

It’s not difficult to see why an underfunded start-up run by two MBAs without industry experience would not be an attractive option. Lacking a cofounder with industry experience Christina and Alex built a team of advisors. They would become disappointed with the support they got from their VC investors.

Christina and Alex could have spent some time gaining industry knowledge by finding employment within the garment industry. It would take years to become an expert, but it is amazing how much you can learn in 12 months if you make learning the focus of your time. You might even be able to convince your employer to pay for external training. My business ethics would say that joining an employer with the sole intention of using them to gain experience knowing that you intend to leave within a short period is a questionable practice. But a bright MBA should be able to deliver value to their employer soon after joining which would balance out the cost-reward equation. Alternatively, you could spend your evenings on Google learning as much as you can about the industry you are about to enter.

Let’s turn our attention to the folks Quincy hired. The team they assembled consisted mainly of industry specialists who because of their backgrounds lacked flexibility and lacked initiative.

In the world of start-ups, employees are expected to be jacks of all trades, taking on multiple responsibilities, and doing whatever needs to be done to move the business forward.

But the Quincy employees, used to the defined roles within the garment industry, pushed back when asked to take on tasks they saw as outside their skill set.

They also seemed to be reluctant to speak up when their industry knowledge could have avoided problems. As demonstrated by the pink lining that stained shirts or the too-small cuffs mentioned in earlier episodes.

Ideally, Quincy should have sought out folks with industry experience and start-up experience. Although people with both types of expertise are few and far between. They were not able to attract enough people who saw Quincy as an excellent opportunity to get in at the start of a disruptive business. Not all veterans with experience lack flexibility and initiative. Offering lower fixed salaries with significant upside bonuses will attract people with the right skills and attitude.

The investors they worked with were clearly impressed by the MVP and initial launch but were skeptical about the ability of Nelson and Wallace to execute. The investors decided to withhold some funds which would be made available subject to performance goals. Although the goals were met, it felt to the founders that they were continually having to sell Quincy as a viable business proposition. The VC funds they worked with were unable to contribute much more than cash. Quincy’s founders had anticipated that given that the VC funds had invested in similar businesses they would be able to provide industry knowledge and contacts. But the investors had not been closely involved in the running of the businesses they funded so they had little to add.

VC funding is seen as the preferred choice for start-ups, but VC funding is not always right for a business. VC investors expect most of the companies they invest in to fail.

They rely on the few that do succeed to generate high returns to offset the losses in less successful investments. Consequently, they will push start-ups to be aggressive, to reach for the sky. Often this is not the ideal strategy for the business. In the case of Quincy, the investors encouraged the business to hold high inventories, stating that stockouts were a disaster for a retailer. Those high inventories ate into Quincy’s cash reserves.

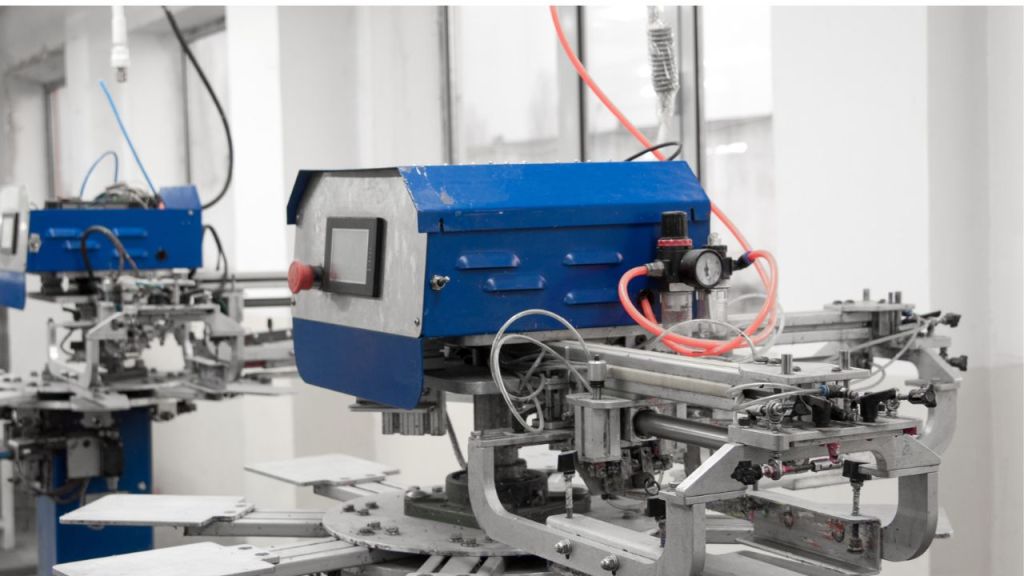

Outsourced manufacturing. The partners Quincy chose to make their garments also proved to be problematic. We learned in earlier episodes how the manufacturers failed to meet their commitments or raised prices beyond those originally quoted. There is not a lot that an underfunded start-up can do in such a situation. Resorting to legal action is impractical. One possible solution would be to offer the production company an equity stake in the business, aligning both parties’ objectives for the fledgling company.

As a CFO, I must wonder how much the optimistic business plan projections contributed to the business’s downfall. In Professor Eisenmann’s book and in the HBS case study we are told that Quincy planned for a 20% return rate versus an industry average of 34%. Their projections for Gross Margin were 57%. In a few minutes on the internet, I learned that the industry average in 2014, two years after Quincy launched, was 37%. EBITDA was expected to be over 30%, again the industry average in 2014 was 12.5%. Quincy’s team did not have anyone with real-world CFO experience. I am sure as part of their MBA both Nelson and Wallace had training in business finance, but the real world and theory can often differ.

I believe that overly optimistic projections, which are common, are dangerous. It gives owners the impression that they have more cushion than they really have.

And we know the financial results achieved by Quincy fell short of expectations.

This leads to problems being brushed aside. Quincy put the issues they experienced during their first season as teething troubles. With more accurate forecasts and reporting, the urgency to fix things would have been greater. They would have started to seek additional funding earlier. The lack of a good grasp of the realities of a business’s financial position is a common failure in start-ups. 50% of business owners do not know if their business is financially viable if the status quo is maintained. A business plan, cash flow forecast, and projections are a must-have for any new venture.

Acknowledgment: Much of the material for this case study came from Professor Eisenmann’s excellent book “Why Start-Ups Fail” There is a lot more to his book than I will cover in this series. Check out his website to learn more.